6.5 KiB

Class patterns

In object-oriented programming, a *class* is an extensible program-code-template for creating objects, providing initial values for state (member variables) and implementations of behavior (member functions or methods).

There's a special syntax construct and a keyword class in JavaScript. But before studying it, we should consider that the term "class" comes the theory of object-oriented programming. The definition is cited above, and it's language-independant.

In JavaScript there are several well-known programming patterns to make classes even without using the class keyword. And here we'll talk about them first.

The class construct will be described in the next chapter, but in JavaScript it's a "syntax sugar" and an extension of one of the patterns that we'll study here.

[cut]

Functional class pattern

The constructor function below can be considered a class according to the definition:

function User(name) {

this.sayHi = function() {

alert(name);

};

}

let user = new User("John");

user.sayHi(); // John

It follows all parts of the definition:

- It is a "program-code-template" for creating objects (callable with

new). - It provides initial values for the state (

namefrom parameters). - It provides methods (

sayHi).

This is called functional class pattern.

In the functional class pattern, local variables and nested functions inside User, that are not assigned to this, are visible from inside, but not accessible by the outer code.

So we can easily add internal functions and variables, like calcAge() here:

function User(name, birthday) {

*!*

// only visible from other methods inside User

function calcAge() {

new Date().getFullYear() - birthday.getFullYear();

}

*/!*

this.sayHi = function() {

alert(name + ', age:' + calcAge());

};

}

let user = new User("John", new Date(2000,0,1));

user.sayHi(); // John

In this code variables name, birthday and the function calcAge() are internal, private to the object. They are only visible from inside of it. The external code that creates the user only can see a public method sayHi.

In works, because functional classes provide a shared lexical environment (of User) for private variables and methods.

Prototype-based classes

Functional class pattern is rarely used, because prototypes are generally better.

Soon you'll see why.

Here's the same class rewritten using prototypes:

function User(name, birthday) {

*!*

this._name = name;

this._birthday = birthday;

*/!*

}

*!*

User.prototype._calcAge = function() {

*/!*

return new Date().getFullYear() - this._birthday.getFullYear();

};

User.prototype.sayHi = function() {

alert(this._name + ', age:' + this._calcAge());

};

let user = new User("John", new Date(2000,0,1));

user.sayHi(); // John

- The constructor

Useronly initializes the current object state. - Methods reside in

User.prototype.

Here methods are technically not inside function User, so they do not share a common lexical environment.

So, there is a widely known agreement that internal properties and methods are prepended with an underscore "_". Like _name or _calcAge(). Technically, that's just an agreement, the outer code still can access them. But most developers recognize the meaning of "_" and try not to touch prefixed properties and methods in the external code.

We already can see benefits over the functional pattern:

- In the functional pattern, each object has its own copy of methods like

this.sayHi = function() {...}. - In the prototypal pattern, there's a common

User.prototypeshared between all user objects.

So the prototypal pattern is more memory-efficient.

...But not only that. Prototypes allow us to setup the inheritance, precisely the same way as built-in JavaScript constructors do. Functional pattern allows to wrap a function into another function, and kind-of emulate inheritance this way, but that's far less effective, so here we won't go into details to save our time.

Prototype-based inheritance for classes

Let's say we have two prototype-based classes.

Rabbit:

function Rabbit(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Rabbit.prototype.jump = function() {

alert(this.name + ' jumps!');

};

let rabbit = new Rabbit("My rabbit");

...And Animal:

function Animal(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function() {

alert(this.name + ' eats.');

};

let animal = new Animal("My animal");

Right now they are fully independent.

But naturally Rabbit is a "subtype" of Animal. In other words, rabbits should be based on animals, have access to methods of Animal and extend them with its own methods.

What does it mean in the language on prototypes?

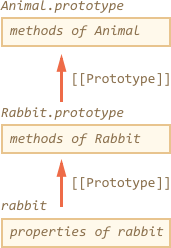

Right now rabbit objects have access to Rabbit.prototype. We should add Animal.prototype to it. So the chain would be rabbit -> Rabbit.prototype -> Animal.prototype.

Like this:

The code example:

// Same Animal as before

function Animal(name) {

this.name = name;

}

// All animals can eat, right?

Animal.prototype.eat = function() {

alert(this.name + ' eats.');

};

// Same Rabbit as before

function Rabbit(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Rabbit.prototype.jump = function() {

alert(this.name + ' jumps!');

};

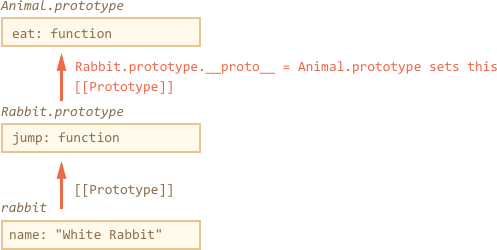

*!*

// setup the inheritance chain

Rabbit.prototype.__proto__ = Animal.prototype; // (*)

*/!*

let rabbit = new Rabbit("White Rabbit");

*!*

rabbit.eat(); // rabbits can eat too

*/!*

rabbit.jump();

The line (*) sets up the prototype chain. So that rabbit first searches methods in Rabbit.prototype, then Animal.prototype. And then, just for completeness, the search may continue in Object.prototype, because Animal.prototype is a regular plain object, so it inherits from it. But that's not painted for brevity.

Here's what the code does:

Summary

The term "class" comes from the object-oriented programming. In JavaScript it usually means the functional class pattern or the prototypal pattern. The prototypal pattern is more powerful and memory-efficient, so it's recommended to stick to it.

According to the prototypal pattern:

- Methods are stored in

Class.prototype. - Prototypes inherit from each other.

In the next chapter we'll study class keyword and construct. It allows to write prototypal classes shorter and provides some additional benefits.