22 KiB

Closure

JavaScript is a very function-oriented language, it gives a lot of freedom. A function can be created at one moment, then passed as a value to another variable or function and called from a totally different place much later.

We know that a function can access variables outside of it. And this feature is used quite often.

But what happens when outer variables change? Does a function get a new value or the old one?

Also, what happens when a variable with the function travels to another place of the code and is called from there -- will it get access to outer variables in the new place?

There is no general programming answer for these questions. Different languages behave differently. Here we'll cover JavaScript.

[cut]

A couple of questions

Let's formulate two questions for the seed, and then study internal mechanics piece-by-piece, so that you will be able to answer them and have no problems with more complex ones in the future.

-

The function

sayHiuses an external variablename. The variable changes before function runs. Will it pick up a new variant?let name = "John"; function sayHi() { alert("Hi, " + name); } name = "Pete"; *!* sayHi(); // what will it show: "John" or "Pete"? */!*Such situations are common in both browser and server-side development. A function may be scheduled to execute later than it is created: on user action or after a network request etc.

So, the question is: does it pick up latest changes?

-

The function

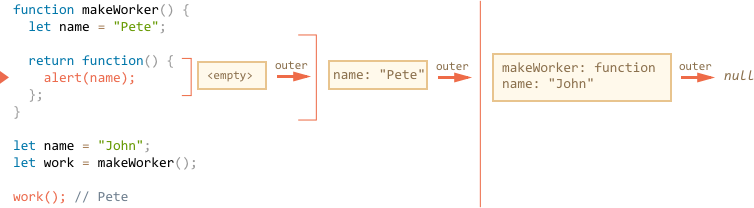

makeWorkermakes another function and returns it. That new function can be called from somewhere else. Will it have access to outer variables from its creation place or the invocation place or maybe both?function makeWorker() { let name = "Pete"; return function() { alert(name); }; } let name = "John"; // create a function let work = makeWorker(); // call it *!* work(); // what will it show? "Pete" (name where created) or "John" (name where called)? */!*

Lexical Environment

To understand what's going on, let's first discuss what a "variable" technically is.

In JavaScript, every running function, code block and the script as a whole have an associated object named Lexical Environment.

The Lexical Environment object consists of two parts:

- Environment Record -- an object that has all local variables as its properties (and some other information like the value of

this). - An reference to the outer lexical environment, usually the one associated with the code lexically right outside of it (outside of the current figure brackets).

So, a "variable" is just a property of the special internal object, Environment Record. "To get or change a variable" means "to get or change the property of that object".

For instance, in this simple code, there is only one Lexical Environment:

This is a so-called global Lexical Environment, associated with the whole script. For browsers, all <script> tags share the same global environment.

On the picture above the rectangle means Environment Record (variable store) and the arrow means the outer reference. The global Lexical Environment has no outer one, so that's null.

Here's the bigger picture of how let variables work:

- When a script starts, the Lexical Environment is empty.

- The

let phrasedefinition appears. Now it initially has no value, soundefinedis stored. - The

phraseis assigned. - The

phrasechanges the value.

Everything looks simple for now, right?

To summarize:

- A variable is a property of a special internal object, associated with the currently executing block/function/script.

- Working with variables is actually working with the properties of that object.

Function Declaration

Function Declarations are special. Unlike let variables, they are processed not when the execution reaches them, but much earlier: when a Lexical Environment is created. For the global Lexical Environment, it means the moment when the script is started.

...And that is why we can call a function declaration before it is defined, like say in the code below:

Here we have say function defined from the beginning of the script, and let appears a bit later.

Inner and outer Lexical Environment

Now we have a call to say() accessing the outer variables let's see the details of what's going on.

When a function runs, a new function Lexical Environment is created automatically for variables and parameters of the call.

Here's the picture for say("John"):

The outer reference points to the environment outside of the function: the global one.

So during the function call we have two Lexical Environments: the inner (for the function call) and the outer (global):

- The inner Lexical Environment corresponds to the current

sayexecution. It has a single variable:name. - The outer Lexical Environment is the "right outside" of the function declaration. Here the function is defined in the global Lexical Environment, so this is it.

When a code wants to access a variable -- it is first searched in the inner Lexical Environment, then in the outer one, and further until the end of the chain.

If a variable is not found anywhere, that's an error in strict mode (without use strict an assignment to an undefined variable is technically possible, but that's a legacy feature, not recommended).

Let's see what it means for our example:

- When the

alertinsidesaywants to accessname, it is found immediately in the function Lexical Environment. - When the code wants to access

phrase, then there is nophraselocally, so follows theouterreference and finds it globally.

Now we can give the answer to the first seed question.

A function sees external variables as they are now.

That's because of the described mechanism. Old variable values are not saved anywhere. When a function wants them, it takes the current values from its own or an outer Lexical Environment.

So the answer is, of course, Pete:

let name = "John";

function sayHi() {

alert("Hi, " + name);

}

name = "Pete"; // (*)

*!*

sayHi(); // Pete

*/!*

The execution flow of the code above:

- The global Lexical Envrionment has

name: "John". - At the line

(*)the global variable is changed, now it hasname: "Pete". - When the function

say(), is executed and takesnamefrom outside. Here that's from the global Lexical Environment where it's already"Pete".

Please note that a new function Lexical Environment is created each time a function runs.

And if a function is called multiple times, then each invocation will have its own Lexical Environment, with local variables and parameters specific for that very run.

"Lexical Environment" is a specification object. We can't get this object in our code and manipulate it directly. JavaScript engines also may optimize it, discard variables that are unused in the code and perform other stuff.

Nested functions

A function is called "nested" when it is created inside another function.

Technically, that is easily possible.

We can use it to organize the code, like this:

function sayHiBye(firstName, lastName) {

// helper nested function to use below

function getFullName() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

alert( "Hello, " + getFullName() );

alert( "Bye, " + getFullName() );

}

Here the nested function getFullName() is made for convenience. It has access to outer variables and so can return the full name.

What's more interesting, a nested function can be returned: as a property of an object or as a result by itself. And then used somewhere else. But no matter where, it still keeps the access to the same outer variables.

An example with a constructor function (from the chapter info:constructor-new):

// constructor function returns a new object

function User(name) {

// the method is created as a nested function

this.sayHi = function() {

alert(name);

};

}

let user = new User("John");

user.sayHi();

An example with returning a function:

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function() {

return count++;

};

}

let counter = makeCounter();

alert( counter() ); // 0

alert( counter() ); // 1

alert( counter() ); // 2

We'll continue on with makeCounter example. It creates the "counter" function that returns the next number on each invocation. Despite being simple, such code structure still has practical applications, for instance, a pseudorandom number generator.

When the inner function runs, the variable in count++ is searched from inside out.

For the example above, the order will be:

- The locals of the nested function.

- The variables of the outer function.

- ...And further until it reaches globals.

As a rule, if an outer variable is modified, then it is changed on the place where it is found. So count++ finds the outer variable and increases it "at place" (as a property of the corresponding Environment Record) every time.

The questions may arise:

- Can we somehow reset the counter from the outer code?

- What if we call

makeCounter()multiple times -- are the resultingcounterfunctions independent or they share the samecount?

Try to answer them before going on reading.

...Are you done?

Okay, here we go with the answers.

- There is no way. The

counteris a local function variable, we can't access it from outside. - For every call to

makeCounter()a new function Lexical Environment is created, with its owncounter. So the resultingcounterfunctions are independent.

Probably, the situation with outer variables is quite clear for you as of now. But my teaching experience shows that still there are problems sometimes. And in more complex situations a solid in-depth understanding of internals may be needed. So here you go.

Environments in detail

For a more in-depth understanding, this section elaborates makeCounter example in detail, adding some missing pieces.

Here's what's going on step-by-step:

-

When the script has just started, there is only global Lexical Environment:

At this moment there is only

makeCounterfunction. And it did not run yet.Now let's add one piece that we didn't cover yet.

All functions "on birth" receive a hidden property

[[Environment]]with the reference to the Lexical Environment of their creation. So a function kind of remembers where it was made. In the future, when the function runs,[[Environment]]is used as the outer lexical reference.Here,

makeCounteris created in the global Lexical Environment, so[[Environment]]keeps the reference to it. -

Then the code runs on, and the call to

makeCounter()is performed. Here's the state when we are at the first line insidemakeCounter():The Lexical Environment for the

makeCounter()call is created.As all Lexical Environments, it stores two things:

- Environment Record with local variables, in our case

countis the only local variable (after the line withlet countis processed). - The outer lexical reference, which is set using

[[Environment]]of the function. Here[[Environment]]ofmakeCounterreferences the global Lexical Environment.

So, now we have two Lexical Environments: the first one is global, the second one is for the current

makeCountercall, with the outer reference to global. - Environment Record with local variables, in our case

-

During the execution of

makeCounter(), a tiny nested function is created.It doesn't matter how the function is created: using Function Declaration or Function Expression or in an object literal as a method. All functions get the

[[Environment]]property that references the Lexical Environment where they are made.For our new nested function that is the current Lexical Environment of

makeCounter():Please note that at the inner function was created, but not yet called. The code inside

function() { return count++; }is not running.So we still have two Lexical Environments. And a function which has

[[Environment]]referencing to the inner one of them. -

As the execution goes on, the call to

makeCounter()finishes, and the result (the tiny nested function) is assigned to the global variablecounter:That function has only one line:

return count++, that will be executed when we run it. -

When the

counter()is called, an "empty" Lexical Environment is created for it. It has no local variables by itself. But the[[Environment]]ofcounteris used for the outer reference, so it has access to the variables of the formermakeCounter()call, where it was created:Now if it accesses a variable, it first searches its own Lexical Environment (empty), then the Lexical Environment of the former

makeCounter()call, then the global one.When it looks for

count, it finds it among the variablesmakeCounter, in the nearest outer Lexical Environment.Please note how memory management works here. When

makeCounter()call finished some time ago, its Lexical Environment was retained in memory, because there's a nested function with[[Environment]]referencing it.Generally, a Lexical Environment object lives until there is a function which may use it. And when there are none, it is cleared.

-

The call to

counter()not only returns the value ofcount, but also increases it. Note that the modification is done "at place". The value ofcountis modified exactly in the environment where it was found.So we return to the previous step with the only change -- the new value of

count. The following calls all do the same. -

Next

counter()invocations do the same.

The answer to the second seed question from the beginning of the chapter should now be obvious.

The work() function in the code below uses the name from the place of its origin through the outer lexical environment reference:

So, the result is "Pete" here.

...But if there were no let name in makeWorker(), then the search would go outside and take the global variable as we can see from the chain above. In that case it would be "John".

There is a general programming term "closure", that developers generally should know.

A [closure](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closure_(computer_programming)) is a function that remembers its outer variables and can access them. In some languages, that's not possible, or a function should be written in a special way to make it happen. But as explained above, in JavaScript all functions are naturally closures (there is only one exclusion, to be covered in <info:new-function>).

That is: they automatically remember where they are created using a hidden `[[Environment]]` property, and all of them can access outer variables.

When on an interview a frontend developer gets a question about "what's a closure?", a valid answer would be a definition of the closure and an explanation that all functions in JavaScript are closures, and maybe few more words about technical details: the `[[Environment]]` property and how Lexical Environments work.

Code blocks and loops, IIFE

The examples above concentrated on functions. But Lexical Environments also exist for code blocks {...}.

They are created when a code block runs and contain block-local variables.

In the example below, when the execution goes into if block, the new Lexical Environment is created for it:

The new Lexical Environment gets the enclosing one as the outer reference, so phrase can be found. But all variables and Function Expressions declared inside if, will reside in that Lexical Environment.

After if finishes, the alert below won't see the user.

For a loop, every run has a separate Lexical Environment. The loop variable is its part:

for(let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// Each loop has its own Lexical Environment

// {i: value}

}

We also can use a "bare" code block to isolate variables.

For instance, in-browser all scripts share the same global area. So if we create a global variable in one script, it becomes available to others. That may be a source of conflicts if two scripts use the same variable name and overwrite each other.

If we don't want that, we can use a code block to isolate the whole script or an area in it:

{

// do some job with local variables that should not be seen outside

let message = "Hello";

alert(message); // Hello

}

alert(message); // Error: message is not defined

In old scripts, you can find immediately-invoked function expressions (abbreviated as IIFE) used for this purpose.

They look like this:

(function() {

let message = "Hello";

alert(message); // Hello

})();

Here a Function Expression is created and immediately called. So the code executes right now and has its own private variables.

The Function Expression is wrapped with brackets (function {...}), because when JavaScript meets "function" in the main code flow, it understands it as a start of Function Declaration. But a Function Declaration must have a name, so there will be an error:

// Error: Unexpected token (

function() { // <-- JavaScript cannot find function name, meets ( and gives error

let message = "Hello";

alert(message); // Hello

}();

We can say "okay, let it be Function Declaration, let's add a name", but it won't work. JavaScript does not allow Function Declarations to be called immediately:

// syntax error because of brackets below

function go() {

}(); // <-- can't call Function Declaration immediately

So the brackets are needed to show JavaScript that the function is created in the context of another expression, and hence it's a Function Expression. Needs no name and can be called immediately.

There are other ways to tell JavaScript that we mean Function Expression:

// Ways to create IIFE

(function() {

alert("Brackets around the function");

}*!*)*/!*();

(function() {

alert("Brackets around the whole thing");

}()*!*)*/!*;

*!*!*/!*function() {

alert("Bitwise NOT operator starts the expression");

}();

*!*+*/!*function() {

alert("Unary plus starts the expression");

}();

In all cases above we declare a Function Expression and run it immediately.

Garbage collection

Lexical Environment objects that we've been talking about are subjects to same memory management rules as regular values.

-

Usually, Lexical Environment is cleaned up after the function run. For instance:

function f() { let value1 = 123; let value2 = 456; } f();It's obvious that both values are unaccessible after the end of

f(). Formally, there are no references to Lexical Environment object with them, so it gets cleaned up. -

But if there's a nested function that is still reachable after the end of

f, then its[[Environment]]reference keeps the outer lexical environment alive as well:function f() { let value = 123; function g() {} *!* return g; */!* } let g = f(); // g is reachable, and keeps the outer lexical environment in memory -

If

f()is called many times, and resulting functions are saved, then the corresponding Lexical Environment objects will also be retained in memory. All 3 of them in the code below:function f() { let value = Math.random(); return function() {}; } // 3 functions in array, every of them links to LexicalEnvrironment // from the corresponding f() run // LE LE LE let arr = [f(), f(), f()]; -

A Lexical Environment object dies when no nested functions remain that reference it. In the code below, after

gbecomes unreachable, it dies with it:function f() { let value = 123; function g() {} return g; } let g = f(); // while g is alive // there corresponding Lexical Environment lives g = null; // ...and now the memory is cleaned up

Real-life optimizations

As we've seen, in theory while a function is alive, all outer variabels are also retained.

But in practice, JavaScript engines try to optimize that. They analyze variable usage and if it's easy to see that an outer variable is not used -- it is removed.

An important side effect in V8 (Chrome, Opera) is that such variable will become unavailable in debugging.

Try running the example below with the open Developer Tools in Chrome.

When it pauses, in console type alert(value).

function f() {

let value = Math.random();

function g() {

debugger; // in console: type alert( value ); No such variable!

}

return g;

}

let g = f();

g();

As you could see -- there is no such variable! In theory, it should be accessible, but the engine optimized it out.

That may lead to funny (if not such time-consuming) debugging issues. One of them -- we can see a same-named outer variable instead of the expected one:

let value = "Surprise!";

function f() {

let value = "the closest value";

function g() {

debugger; // in console: type alert( value ); Surprise!

}

return g;

}

let g = f();

g();

This feature of V8 is good to know. If you are debugging with Chrome/Opera, sooner or later you will meet it.

That is not a bug of debugger, but a special feature of V8. Maybe it will be changed sometimes.

You always can check for it by running examples on this page.